Tags

DEstruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum, Edwin Athelstone, John Martin, John Singer Sargent, Pliny the Elder, Pliny the Younger, Royal Academy, Somerset Museum, South West Heritage Trust, Tate Britain, Tate Gallery, Taunton Castle, Tom Mayberry

This is the title of a huge painting by John Martin (1789-1854), currently on loan from the Tate Gallery to the Museum of Somerset, and on show there (Taunton Castle) until 1st June. Yesterday, as the first half of what was for me an art-full day, I went there to a talk about Martin, his friends, and his life (including local connections) given by the excellent Tom Mayberry, recently retired from his post of CEO to the South West Heritage Trust, after 43 years working there. Afterwards, Tom led us into the temporary exhibition space where the painting is on show.

It was perhaps appropriate that the talk should take place in what used to be the school room in the castle.

This is what greets the visitor to the exhibition. The image is a video, and a rather noisy one at that.

The exhibition comprises much-reduced photographic copies of some of his best-known works, and some text. The only original painting is that of the theme.

Martin’s humble origins meant that he was unable to follow a conventional artist’s training, and his individualistic propensity to portray huge dramatic settings and tiny figures, though frowned upon by the cognoscenti, was loved by the general public. Although some of his paintings were accepted by the Royal Academy, he was never invited to become a member.

One of his earliest successful works is The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Of those mentioned by Tom Mayberry, and reproduced photographically in the exhibition, Belshazzar’s Feast (160 x 249 cm) was one of my favourites – and apparently that of the Victorians.

A good friend of Martin, living in Taunton, was Edwin Athelstone, an epic poet of rather less talent than the artist. He often wrote poems to match his friend’s work, and as one approaches the painting, this extract from his 12-book poem on the volcanic disaster leads one to Martin’s work on one side.

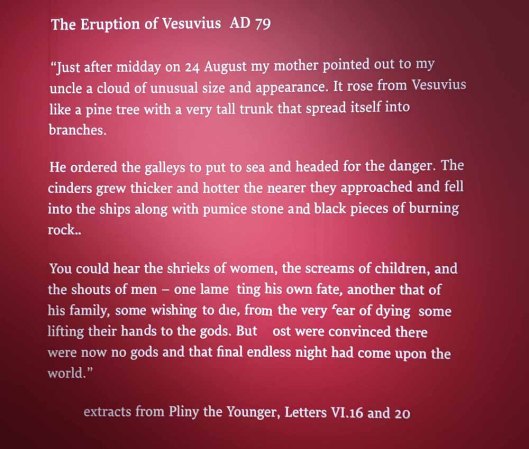

On the other side is this extract from Pliny the Younger’s description of the eruption of Vesuvius, which he had observed, and in which his uncle, Pliny the Elder, perished.

The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum is 160 cm by 250 cm. It was heavily damaged in the 1928 Thames Flood, and was restored brilliantly in 2011, using among other things Martin’s own smaller scale copy as a model. The colours here sadly do not in any way reflect the richness of the reds. My header picture, of the photographic reproduction, is somewhat more faithful.

Martin prepared a numbered diagrammatic guide to his painting.

He didn’t limit himself to painting. This plan for a metropolitan railway for London was ignored, but he foresaw what would come about decades later.

He also produced vast number of mezzotints, for a variety of settings.

His works are scattered all over the world, in public settings and in private hands. But a trilogy of his late works, also huge, are in the Tate Gallery, which I shall certainly make time to visit on a future visit to London.

An earlier work, 1841, was Pandemonium. The figure is Satan.

The exhibition concludes with a few parodies, including:

Except that the final piece of text is:

In the evening I went to a local showing of an Exhibition on Screen about the American painter, John Singer Sargent, and his beautiful works. While the commentary lauded his wonderful treatment of fabrics and fashion, I enjoyed as much how he captured the interesting faces of his subjects. The film was based on two exhibitions, one of which is currently on at Tate Britain until 7th July. (The Guardian reviewer hated it!)

Fascinating…..thank you for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting post. We like Sargent both for the faces and the wonderful fabrics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed hearing about John Martin and seeing samples of his majestic works. I must look out for his trilogy in the Tate Gallery, London.

I thought the Singer Sargent exhibition was well worth a visit, despite having read a very critical review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I seem to remember you said you have enjoyed your visit to the Sargent exhibition. As for the Martin, perhaps we could go together on 18.5…

LikeLike

Merci de m’avoir fait découvrir John Martin et ses oeuvres monumentales.

Christine

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a discovery for me, as well!

LikeLike

wow, would love to see . The one painting in the black frame is just ???? Beautiful amazing…

LikeLike

Your blog is fantastic! I cannot believe that Mr. Martin was never accepted into the Royal Society ! His paintings are unworldly, mysterious and bold. My family recently visited Pompeii and were so impressed with no words to really explain how they felt. I am an archaeologist fan and am always finding new material to read. Do you subscribe to the Archaeology magazine? A must! Pliny …. how wonderful to have this first witness account. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind words, Wendy. No, I don’ know the journal you mention. The painting has certainly made me want to visit Pompeii though.

LikeLike

Pingback: France 2024 – 1. London to Lozère | Musiewild's blog